| Jonah's Aquarium |

jonahsaquarium.com |

Spawning the Rare Pygmy Madtom, Noturus

stanauli

by J.R. Shute

From the Conservation Fisheries,

Inc. Newsletter #2,

1 December, 2000. Used here by permission.

For the past several years CFI has

been working to develop techniques to induce spawning in captive

madtoms. In the past, we have been very successful propagating

madtoms from wild collected eggs. While this has worked well for

a couple of species, where the situation allows for the collection

of wild nests, we could foresee that there would be cases where

this would not be possible. Such a scenario would involve species

that are so rare that even if we were able to locate nests, these

should not be collected for fear of further endangering the population.

This is exactly the case for the pygmy madtom.

Noturus stanauli (click image to left for a full-size image) is known

from only two widely separated localities in the Clinch and Duck

rivers of the Tennessee Drainage. A search of the literature and

museum records revealed that only about 25 museum specimens existed,

and probably fewer than 50 individuals have ever been collected!

This is in spite of extensive surveys by many fish folks collecting

at both known localities and other nearby sites. Obviously, this

is easily one of the rarest fishes in North America!

Noturus stanauli (click image to left for a full-size image) is known

from only two widely separated localities in the Clinch and Duck

rivers of the Tennessee Drainage. A search of the literature and

museum records revealed that only about 25 museum specimens existed,

and probably fewer than 50 individuals have ever been collected!

This is in spite of extensive surveys by many fish folks collecting

at both known localities and other nearby sites. Obviously, this

is easily one of the rarest fishes in North America!

The pygmy madtom is the smallest member

of the genus Noturus. Adults are less than 50mm total length

(TL). They are dark brown dorsally and nearly white ventrally.

This contrast of dark and light is quite striking. Almost nothing

is known of the biology of this rare madtom. Most specimens have

been collected over shallow, fine gravel shoals with moderate

to swift flow, usually near the stream bank.

For years we have wondered about the

possibility of propagating pygmy madtoms. It was clear that the

species was too rare to think we would find nests to collect

and rear. We have had limited success spawning other madtoms in

our hatchery, mostly as a result of injecting hormones. Clearly,

madtoms could be spawned in aquaria, but because of the rarity

of this fish, and our reluctance to handle them, we would hope

to find a natural trigger to induce spawning in these miniature

catfish.

Our chance came this past spring.

On March 25, 2000, Dr. Rick Mayden and crew were in our area collecting

fish to photograph for his upcoming book on the freshwater fishes

of Alabama. The day before we had been out helping them collect

snail darters, Percina tanasi in the Holston River. The

following day, they made a collection in the upper Clinch River.

Later that day we got a call from Rick. They had managed to collect

two pygmy madtoms! They were aware of our efforts to propagate

madtoms and told us that they would turn the specimens over to

CFI. CFI is covered under the necessary federal and state

permits to handle these federally protected species.

We quarantined the two specimens in

a 55 gallon aquarium. One of the two madtoms was considerably

smaller than the other (the smaller was approximately 30 mm and

the larger was around 35 mm TL). Since pygmy madtoms are thought

to have a short, one-year lifespan, we were hopeful that the size

difference was a gender difference, rather than an age difference.

The aquarium was filtered with a large,

air driven, sponge filter. A natural gravel and sand substrate

was provided along with flat rocks and other cover items. The

fish were fed heavily with live blackworms, Daphnia, mosquito

larvae and frozen bloodworms (chironomid larvae). Both individuals

adapted well and slowly increased in size.

By early July, the larger specimen

was becoming obviously gravid. The smaller one showed no signs

of filling out. Also, for the first time since they were placed

into the aquarium, they began to spend time under the same cover

objects. At this point, we provided more cover, including empty

mussel shells and a 6x6î, unglazed ceramic floor tile. More

current was added to the tank, using a small submersible water

pump.

Within a couple of days, the pair (at

least we hoped they were a pair!) took up residence under the

floor tile. Based on our other aquarium experiences, we had discovered

that freshly laid madtom eggs are very difficult to handle and

are much more likely to develop problems than ones that are several

days old. Because of this, we chose to leave the fish undisturbed

for about a week in hopes that if they did spawn, the eggs would

stand a better chance of survival.

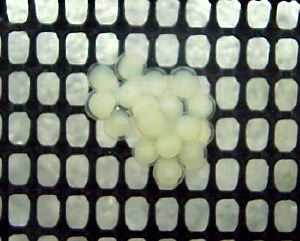

On July 11th, we checked under the

floor tile and found the male guarding a small clutch of eggs!

The female was under an adjacent rock. The eggs were removed from

the custody of the male and transferred to a plastic incubation

tray filled with water from the parentsí tank. There were

10 live eggs and three empty chorions. The eggs measured approximately

3.8 mm in total diameter. Despite the small size of the pygmy

madtom, the eggs are nearly as large as other madtoms weíve

had experience with. The eggs appeared to have been laid at least

a couple of days earlier, and some showed distinct embryonic development.

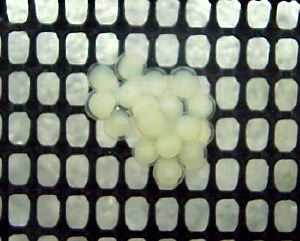

After examining and measuring the eggs,

they were placed onto a hatching platform, dubbed by Pat, a ìmadtom

egg wagonî.  The ìwagonî

was constructed using plastic mesh (3x4mm) and PVC tubing. The

platform was constructed to provide water movement all around

the eggs, even from below. Water movement was facilitated using

a small air stone placed near the eggs.

The ìwagonî

was constructed using plastic mesh (3x4mm) and PVC tubing. The

platform was constructed to provide water movement all around

the eggs, even from below. Water movement was facilitated using

a small air stone placed near the eggs.

Over the next few days several of the

eggs turned opaque and died. Leaving dead eggs in the clutch invites

fungal infection of the good eggs, so these were carefully removed

by pipette, or by inserting the needle from a syringe into the

egg and removing the contents. We were very careful not to damage

adjacent eggs..

The first egg hatched on July 18th

and by the next day, the rest had hatched. At this point, we were

down to four larvae. It was not clear if development was progressing

normally in the eggs that died, or if they were even fertile.

Our reluctance to disturb the developing eggs prevented us from

close observation.

Over the next couple of days, the baby

madtoms looked great. Because the larvae have large yolk sacs

(as all madtoms do), feeding was not necessary until the larvae

began actively swimming.

By July 24th, one of the four larvae

had died. This was right at the stage where the larvae were beginning

their transition from reliance on their yolk to feeding on their

own. The remaining three looked fine and were now accepting newly

hatched Artemia nauplii.

On July 29th, a second nest was discovered,

being guarded by the male pygmy madtom. We had noticed the female

still appeared to be somewhat gravid after the first spawn and

were hopeful that a second spawn was possible. This nest was somewhat

larger than the first, consisting of19 eggs. At the time we discovered

the nest, these eggs were probably at about the same stage of

development as the first clutch.

The second

clutch of eggs were treated much the same as the first clutch.

Again, there were some egg losses over the next couple of days,

but this time we managed to bring 10 eggs to hatching! The

first eggs hatched on August 8th, 10 days after collection. The

spawning adults and incubated eggs were held at approximately

73 degrees F. At this point, the babies from the first spawn measured

18 mm TL!

The second

clutch of eggs were treated much the same as the first clutch.

Again, there were some egg losses over the next couple of days,

but this time we managed to bring 10 eggs to hatching! The

first eggs hatched on August 8th, 10 days after collection. The

spawning adults and incubated eggs were held at approximately

73 degrees F. At this point, the babies from the first spawn measured

18 mm TL!

As the young madtoms grew, they were

put together in a single 20 gallon aquarium which is part

of a much larger aquarium system, and that is where we currently

keep them. The young madtoms have adapted well to chopped, live

blackworms. While the madtoms are rarely seen out from under cover,

they do tend to be most active shortly after the lights go out

in the early evening. For this reason, we believe that pygmy madtoms

may be crepuscular.

At the time of this writing, all 13

madtoms are doing great. They now measure 35 mm TL, which is as

large, or larger than the adults we received from the Clinch River

in March. In October, one of the parents died (itís not

clear which one at this point). The remaining adult still looks

good and is probably the oldest living pygmy madtom in the world!

Our experience here opens up the possibility

for reintroduction work with this and other rare madtoms. Already,

we are able to look at several big-river sites and hope that some

day they might serve as potential homes to this rare fish that

almost certainly inhabited much of the upper Tennessee River in

the past.

Conservation Fisheries, Inc.

is a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of

aquatic biodiversity in the southeastern United States. CFI's

work with the captive propagation of rare, threatened, and endangered

species of fish is designed to ensure their continued survival

in the wild.

Jonah's Aquarium

Menu

jonahsaquarium.com

-

Noturus stanauli (click image to left for a full-size image) is known

from only two widely separated localities in the Clinch and Duck

rivers of the Tennessee Drainage. A search of the literature and

museum records revealed that only about 25 museum specimens existed,

and probably fewer than 50 individuals have ever been collected!

This is in spite of extensive surveys by many fish folks collecting

at both known localities and other nearby sites. Obviously, this

is easily one of the rarest fishes in North America!

Noturus stanauli (click image to left for a full-size image) is known

from only two widely separated localities in the Clinch and Duck

rivers of the Tennessee Drainage. A search of the literature and

museum records revealed that only about 25 museum specimens existed,

and probably fewer than 50 individuals have ever been collected!

This is in spite of extensive surveys by many fish folks collecting

at both known localities and other nearby sites. Obviously, this

is easily one of the rarest fishes in North America! The ìwagonî

was constructed using plastic mesh (3x4mm) and PVC tubing. The

platform was constructed to provide water movement all around

the eggs, even from below. Water movement was facilitated using

a small air stone placed near the eggs.

The ìwagonî

was constructed using plastic mesh (3x4mm) and PVC tubing. The

platform was constructed to provide water movement all around

the eggs, even from below. Water movement was facilitated using

a small air stone placed near the eggs. The second

clutch of eggs were treated much the same as the first clutch.

Again, there were some egg losses over the next couple of days,

but this time we managed to bring 10 eggs to hatching! The

first eggs hatched on August 8th, 10 days after collection. The

spawning adults and incubated eggs were held at approximately

73 degrees F. At this point, the babies from the first spawn measured

18 mm TL!

The second

clutch of eggs were treated much the same as the first clutch.

Again, there were some egg losses over the next couple of days,

but this time we managed to bring 10 eggs to hatching! The

first eggs hatched on August 8th, 10 days after collection. The

spawning adults and incubated eggs were held at approximately

73 degrees F. At this point, the babies from the first spawn measured

18 mm TL!